In Many Cities, "Pandemic Pricing" Is Over

Actual v. Projected Rent Prices

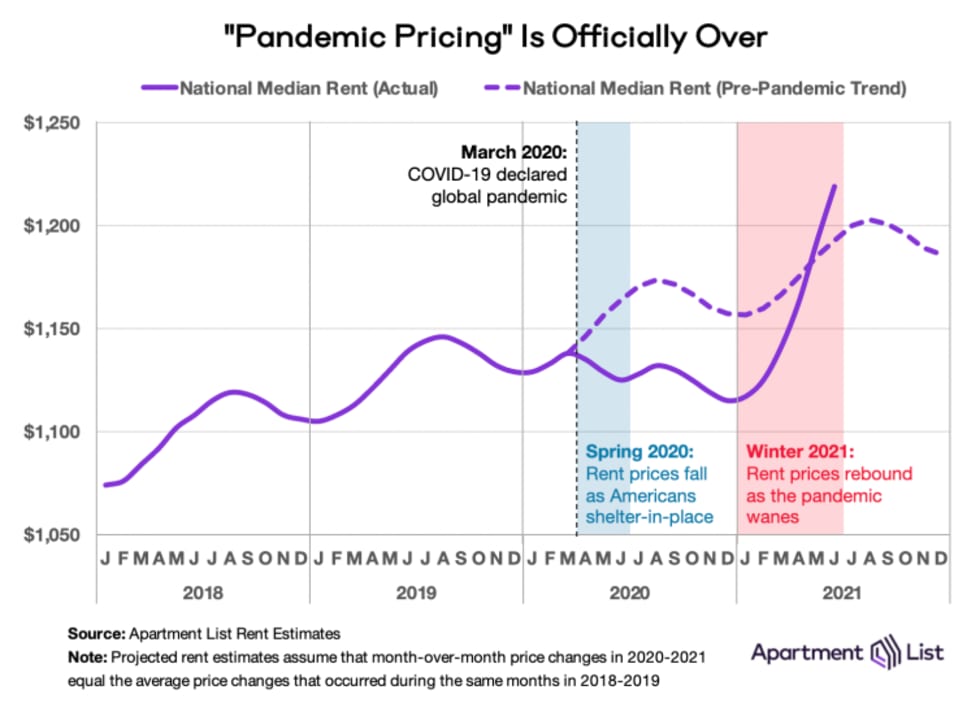

To assess how severely the rental market has been disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, and how quickly it is returning to pre-pandemic prices, we use historical rent data to estimate “projected” rent prices from April 2020 onward. These projections assume that rent growth in 2020 and 2021 mirrors pre-pandemic growth and follows typical seasonal trends in each city studied. For more details on these projections, see the Methodology section below.

As of May 2021, Our National Rent Index Has Fully Rebounded from the Pandemic

Following Spring 2020, when the pandemic drove rent prices down during what is usually the busiest season for the rental market, our national index hovered around 4 percent below its projected level for the remainder of the year. But a rapid rebound in the first half of 2021 has wiped out that price gap. Fourteen months after the pandemic first rattled the rental industry, May 2021 was the first month where rent prices caught back up with expectations; the national median rent price reached $1,189, just above the projected price of $1,185.

Local Rental Markets Are Recovering At Different Rates

The pandemic’s local effect on rent prices has varied dramatically from city to city. Almost every city experienced “pandemic pricing,” defined conservatively as rent prices falling at least 1 percent below seasonal projections at any point from April to December 2020. But the severity of pandemic pricing, and the amount of time it takes each city to recover from it, has differed greatly across place.

Over a year after the start of the pandemic, cities find themselves in one of three camps:

1. Cities where rent growth was uninterrupted by the pandemic

Nine cities, including Greensboro and El Paso below, saw rent prices rise throughout the pandemic. Here “pandemic pricing” was non-existent. Rent growth continued (or in some cases accelerated) even as local economies struggled with the pandemic. The other seven cities exhibiting this pattern are Arlington, TX; Lexington, KY; Norfolk, VA; Spokane, WA; Tucson, AZ; Tulsa, OK; and Wichita, KS.

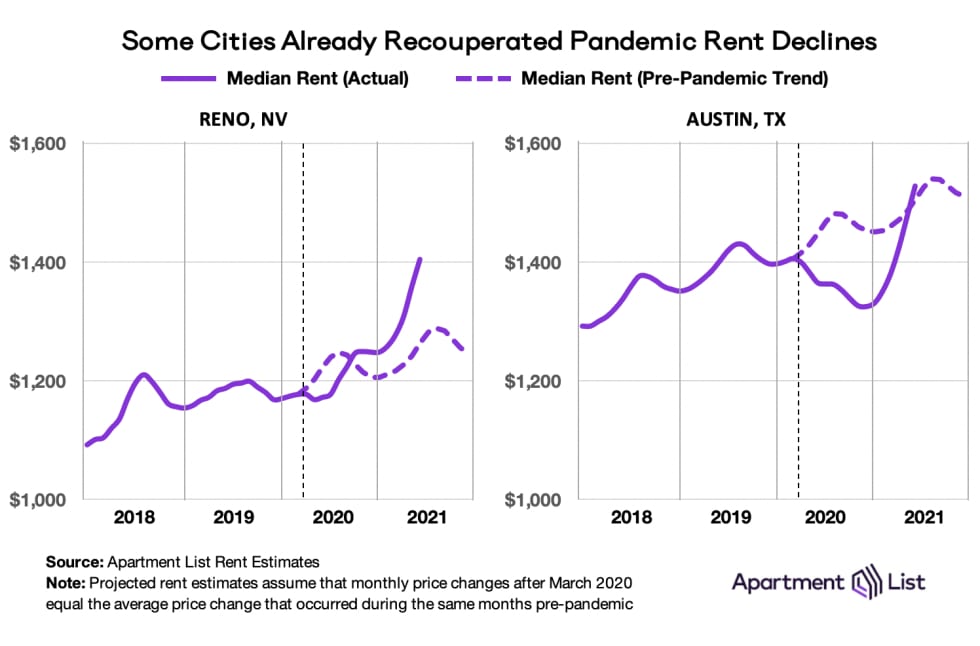

2. Cities where rent prices have fully rebounded from “pandemic pricing”

The vast majority of cities experienced pandemic-driven rent drops in 2020, but in many, prices have already bounced back and now exceed pre-pandemic projections. This includes some smaller cities like Reno: relatively affordable markets that swelled in popularity last year when the pandemic shut down big-city amenities and drove many to seek more spacious homes. But it also includes larger, pricier cities like Austin, where price drops were sharper and lasted nearly a full year before rebounding quickly in the past several months.

3. Cities where rent prices remain below pre-pandemic projections

In 21 of the nation’s largest and most expensive markets, prices are quickly rising but remain below projections. These cities saw the steepest price cuts last year, in part because the immediate shift to remote work reduced demand for expensive housing in their central business districts. While prices are rising today, some cities like Seattle still have a long way to go: as of June 2021 there is a 14 percent gap between actual and projected prices in Seattle. Others like Denver will be back to projected prices in the coming months.

How Far Behind Are the Cities Where Pandemic Pricing Is Still In Effect?

As of June 2021, there are 21 major cities where rents remain below pre-pandemic projections. Here, apartments are cheaper today than they would have been had rent growth in 2020 and 2021 followed historic seasonal trends. This discount is already negligible in cities like Nashville, Santa Ana, and Philadelphia, where actual rents are less than one percent below projected ones. But in other cities like San Francisco, Seattle, and New York, there remains a significant gap.

Although the San Francisco rental market has been rebounding for several months, prices are still 16.2 percent below projection. The city’s current median rent is $2,301, but had prices grown according to normal trends, that median could have been as high as $2,745. Significant gaps are found in other cities across the Bay Area where prices fell sharply early in the pandemic (i.e., Oakland, San Jose, and Fremont), as well as Seattle and many of the largest cities stretching between Boston and Washington, D.C. Meanwhile, smaller gaps persist in regional job hubs like Pittsburgh, Portland, and St. Paul, but at the rate that rents are currently rising in these places, we expect this gap to disappear within the coming months.

Another way to evaluate this rent rebound is to compare today’s actual rent prices to those of March 2020: the last “pre-pandemic” price point in our data. There are several cities - Chicago, Denver, Pittsburgh, for example - where apartments are more expensive today than they were pre-pandemic, but remain cheaper than their projected price. In Pittsburgh, the median as of June 2021 ($1,100) is higher than it was in March 2020 ($1,050) but lower than it would be if we extrapolated that March 2020 price forward to present day using historical data ($1,127). This nuance is important for distinguishing between cities that are more expensive than they were pre-pandemic versus those that are more expensive than they likely would have been in the absence of a pandemic.

Methodology

This analysis compares current and projected median rent prices, nationally and for many major cities across the country. Current rents are calculated according to our rent estimate methodology and are available for download from our data homepage. Projected rents begin in April 2020 by extrapolating forward the March 2020 median rent according to pre-pandemic seasonal trends. Monthly rent growth in April 2020 is equal to the average monthly growth in April 2018 and April 2019; growth in May 2020 is equal to the average of May 2018 and 2019, and so on. We chose this approach because month and price change are highly correlated in the rental market. This strong seasonal effect was consistent in the years leading up to the pandemic. We also tested more sophisticated forecasting methods, including models that decomposed seasonal trends and down-weighted older data points, and as these yielded similar results we prioritized simplicity and transparency in choosing a simple averaging approach.

Share this Article